Negronis all round: simulation recovery of a discrete model 🍹

David Hodgson

2026-01-14

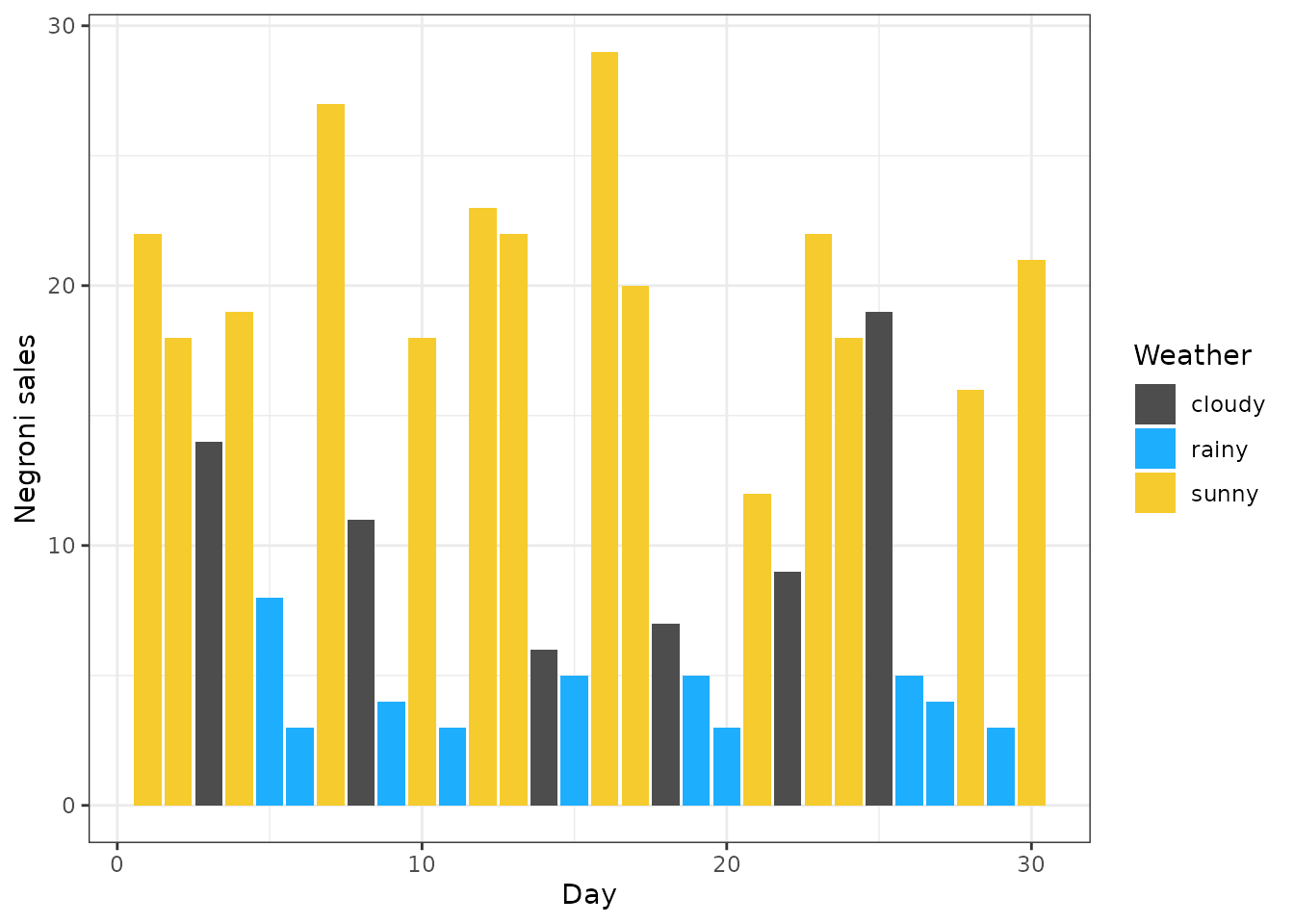

Example2.RmdThis vignette demonstrates how to recover a discrete latent variable model using simulated data on daily weather conditions and associated Negroni sales. The weather per day is a latent variable () that can take one of three states:

- Sunny ☀️,

- Cloudy ☁️

- Rainy 💧

and each state has its own distribution of Negroni sales 🍹. We’ll show how to infer the weather state for each day based on observed Negroni sales using a probabilistic modeling framework.

2. Simulated data

We simulate the dataset as follows:

Each day of a month has an unobserved (“latent”) weather state ($W_i ${🌧️, ☁️, ☀️ }). We assume each weather is equally likely to happen on each day. For each weather condition, we have a different distribution of Negroni sales each day which we assume follows:

- Sunny ☀️:

- Cloudy ☁️:

- Rainy 💧:

Based on this,let’s simulate some data:

set.seed(42)

# Parameters

n_days <- 30

weather_states <- c("sunny", "cloudy", "rainy")

lambda <- c(20, 10, 4) # Poisson means for each weather state

prior_probs <- c(0.33, 0.33, 0.33) # Prior probabilities for each weather state

# Generate latent weather states

latent_weather <- sample(weather_states, size = n_days, replace = TRUE, prob = prior_probs)

# Generate observed Negroni sales

sales <- sapply(latent_weather, function(w) {

rpois(1, lambda[which(weather_states == w)])

})

# Combine into a data frame

data <- data.frame(day = 1:n_days, sales = sales, weather = latent_weather)

library(ggplot2)

# plot!

data %>%

ggplot() +

geom_col(aes(x = day, y = sales, fill = weather)) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("sunny" = "#f6cb2e", "cloudy" = "gray30", "rainy" = "#1eaefe")) +

labs(x = "Day", y = "Negroni sales", fill = "Weather") + theme_bw()

3. Simulation recovery

3.1 Description of the model

In our Bayesian model we assume that Observed Negroi Sales () are Poisson distributed with a rate parameter that depends on the latent weather state . That is the likelihood is Poisson with rate for each weather state . We assume the priors on the rate parameters . Finally, the prior distribution posterior distribution is given as the product of the likelihood and prior for each weather state .

3.2 Steps to Recover :

To recover the latent weather states, we use a Bayesian model with the following components:

Define the Likelihood Function: Implement the Poisson likelihood for given for each weather state .

Calculate the posterior probabilities: Use the likelihood and prior to compute the posterior probabilities for each using Bayes’ Rule.

Infer the model probable state per day: Assign each day to the weather state w with the highest posterior probability.

Repeat for all days: Perform the above inference for all days in the dataset to recover the sequence of latent weather states.

data_t <- list(

N = nrow(data),

y = data$sale

)

# Add all of these entries into a model list

model <- list(

# 1. Parameter Bounds (lowerParSupport_fitted and upperParSupport_fitted)

# These define the lower and upper bounds for the three model parameters: w_r, w_c, and w_s.

# w_r, w_c, and w_s are restricted to lie between 0 and 100.

# This ensures that the values for each parameter remain within a reasonable range during model fitting or sampling.

lowerParSupport_fitted = c(0, 0, 0),

upperParSupport_fitted = c(100, 100, 100),

# 2. Parameter Names (namesOfParameters)

# namesOfParameters is a vector containing the names of the three parameters that the model will estimate:

#w_r: the rate associated with the first category (discrete value 1),

#w_c: the rate associated with the second category (discrete value 2),

#w_s: the rate associated with the third category (discrete value 3).

namesOfParameters = c("w_r", "w_c", "w_s"),

## 3. Discrete Length (discrete_length)

# This is the length of the discrete sequence (i.e., the number of data points N). The model assumes that discrete has a length of 30, meaning there are 30 discrete latent variables to be inferred from the data, corresponding to 30 days.

discrete_length = 30,

# 4. Sampling from Prior Distributions (samplePriorDistributions)

## The function samplePriorDistributions generates prior samples for the parameters w_r, w_c, and w_s.

## It samples each parameter independently from a uniform distribution between 0 and 100.

samplePriorDistributions = function(datalist) {

runif(3, 0, 100)

},

# 5. Evaluating the Log-Prior (evaluateLogPrior)

# The function evaluateLogPrior calculates the log-prior of the model based on the parameters params (a vector containing w_r, w_c, and w_s).

evaluateLogPrior = function(params, discrete, datalist) {

lpr <- dunif( params, 0, 100, TRUE) %>% sum

if (!(params[1] < params[2] & params[2] < params[3])) {

lpr <- log(0)

}

lpr

},

# 6. Initialising the Discrete Latent Variables (initialiseDiscrete)

# initialiseDiscrete initializes the discrete latent variables for each data point.

# The function samples N values (where N = 30 in this case) from the set {1, 2, 3}, assigning each data point to one of the three possible categories. This is done randomly with replacement.

initialiseDiscrete = function(datalist) {

require(purrr)

N <- datalist$N

discrete <- sample(1:3, N, replace = TRUE)

discrete

},

#7. Discrete Sampling (discreteSampling)

# discreteSampling is a function that updates the latent discrete variable using a random walk approach. It applies a random operation (based on the value of u) to the current state of the discrete vector:

#With probability 1/3, it randomly resamples one element of the discrete vector and assigns it to a new value from the set {1, 2, 3}.

#With probability 1/3, it swaps the values of two randomly selected elements in the discrete vector.

#With the remaining probability, no change is made to the discrete vector.

discreteSampling = function(discrete, datalist) {

u <- runif(1)

N <- datalist$N

# resample

if (u < 0.33) {

j <- sample(1:N, 1)

discrete[j] <- sample(1:3, 1)

# swap

} else if(u < 0.66) {

j_idx <- sample(1:N, 2)

j_idx_1 <- discrete[j_idx[1]]

discrete[j_idx[1]] <- discrete[j_idx[2]]

discrete[j_idx[2]] <- j_idx_1

} else {

# nothing happens!

}

return(discrete)

},

# 8. Evaluating the Log-Likelihood (evaluateLogLikelihood)

# The function evaluateLogLikelihood calculates the log-likelihood for a set of parameter values params, given the observed data and the current state of the discrete latent variables.

# w_r, w_c, and w_s are the three model parameters (rates).

# The function iterates over each data point (from 1 to N, where N = 30), checking which category (discrete[i]) the data point belongs to.

#For each category (1, 2, or 3), it calculates the log-likelihood of the observed data point datalist$y[i] under the corresponding Poisson distribution with the rate parameter (w_r, w_c, or w_s).

#The log-likelihood is accumulated and returned as the total log-likelihood for the model.

evaluateLogLikelihood = function(params, discrete, covariance, datalist) {

w_r <- params[1]

w_c <- params[2]

w_s <- params[3]

N <- datalist$N

ll <- 0;

for (i in 1:N) {

if (discrete[i] == 1) {

ll <- ll + dpois(datalist$y[i], w_r, log = TRUE)

} else if (discrete[i] == 2) {

ll <- ll + dpois(datalist$y[i], w_c, log = TRUE)

} else {

ll <- ll + dpois(datalist$y[i], w_s, log = TRUE)

}

}

ll

}

)3.3. Settings and run model

Select the run time, chains, number of cores, burnin and thinning for the model.

# Settings used for the ptmc model

settings <- list(

numberChainRuns = 2,

numberCores = mc.cores,

numberTempChains = 10,

iterations = 100000,

burninPosterior = 50000,

thin = 100

)

post <- ptmc_discrete_func(model=model, data=data_t, settings=settings)4. Analyse the posterior distributions

ptmc_discrete_func returns a list of with entries:

- : An MCMC object with posterior samples of the model parameters.

- : A list of discrete states generated during the simulation for each chain.

- : A data frame of log-posterior values, with columns representing different chains and rows representing samples.

- : A data frame of temperatures for each chain at each sample.

- : A data frame of acceptance rates for each chain at each sample.

- : A list containing the parameter values for each chain.

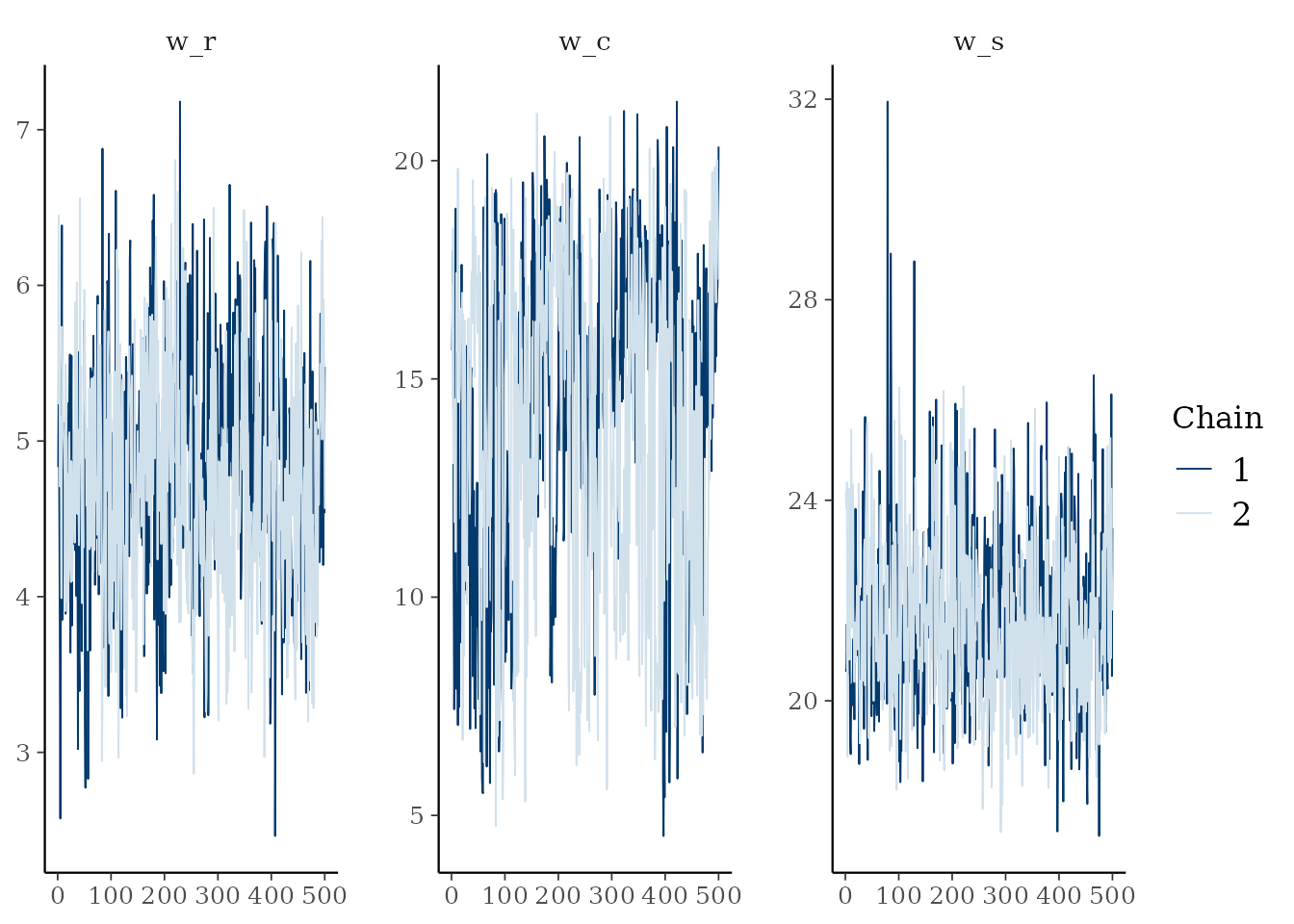

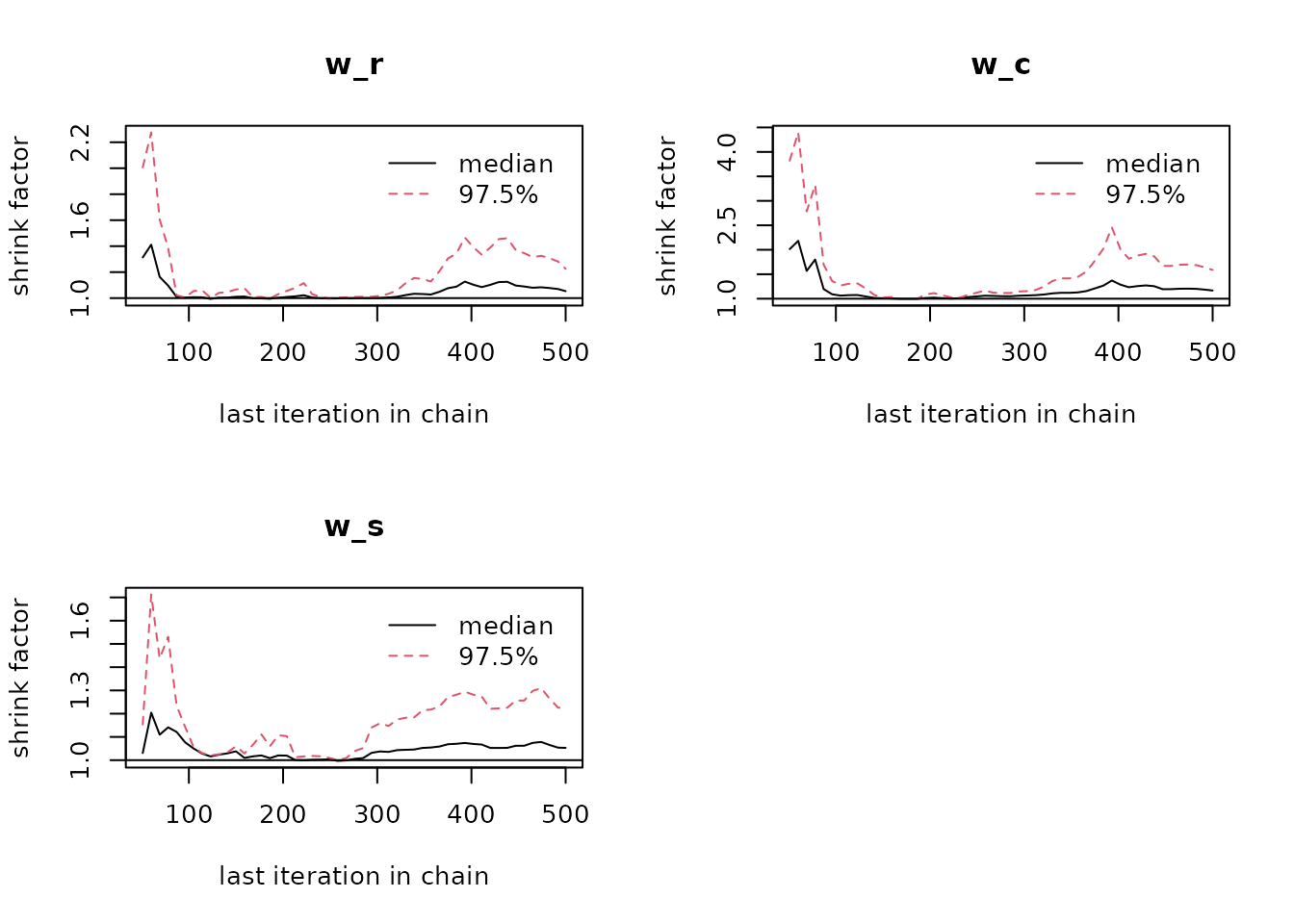

. The first entry is post$mcmc a mcmc or mcmc.list

object (from the coda package). You can plot these and

calculate convergence diagnostics using coda functions:

# Plot the Gelman-Rubin diagnostic for the parameters

gelman.plot(post$mcmc)

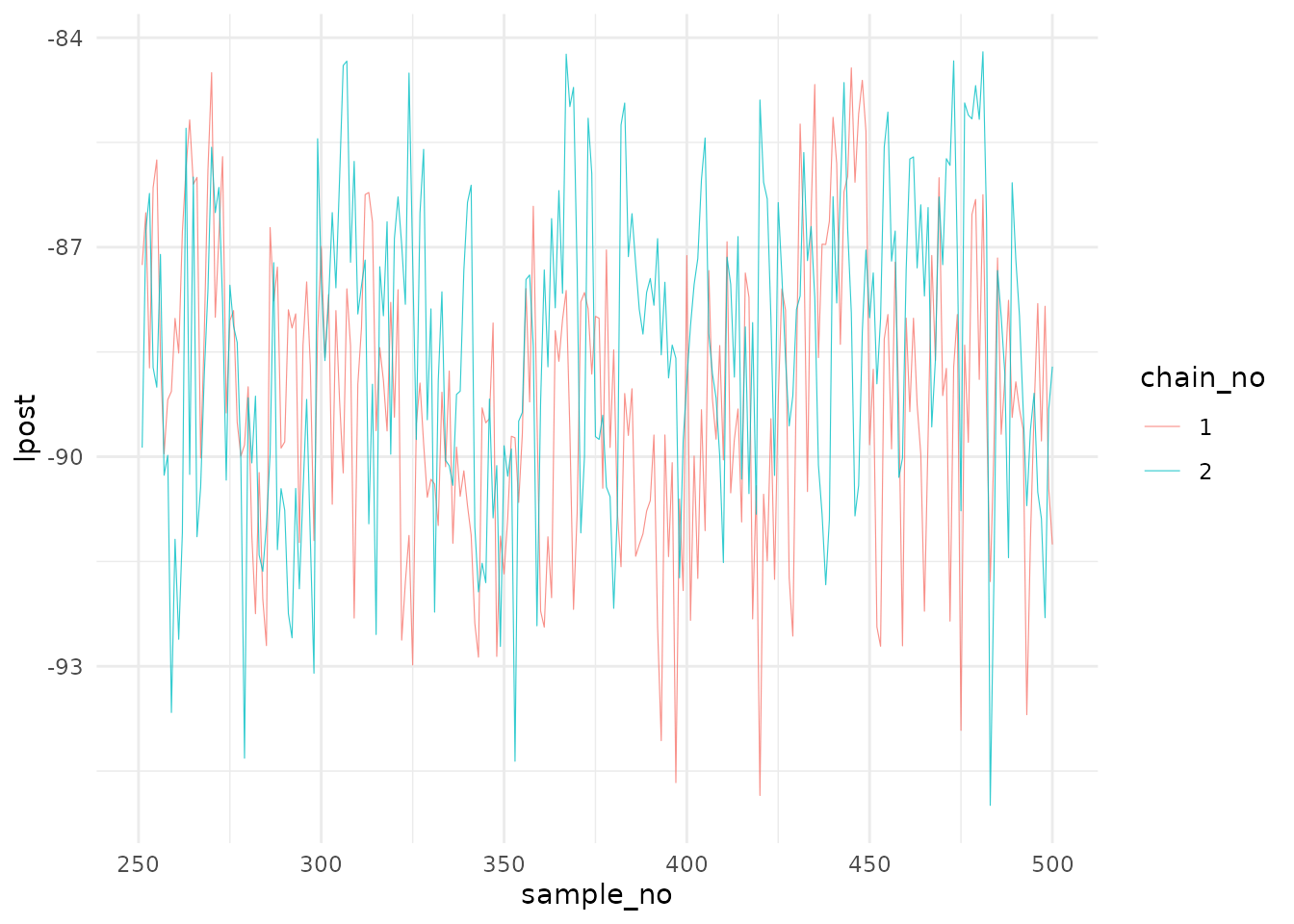

The next entry is post$lpost and is long table dataframe

of the log-posterior values. These values can be easily plotted using

ggplot2:

library(ggplot2)

# Plot of the logposterior for the three chains

lpost_conv <- post$lpost %>% filter(sample_no>250)

logpostplot <- ggplot(lpost_conv, aes(x = sample_no, y = lpost)) +

geom_line(aes(color = chain_no), size = 0.2, alpha=0.8) +

theme_minimal()

logpostplot

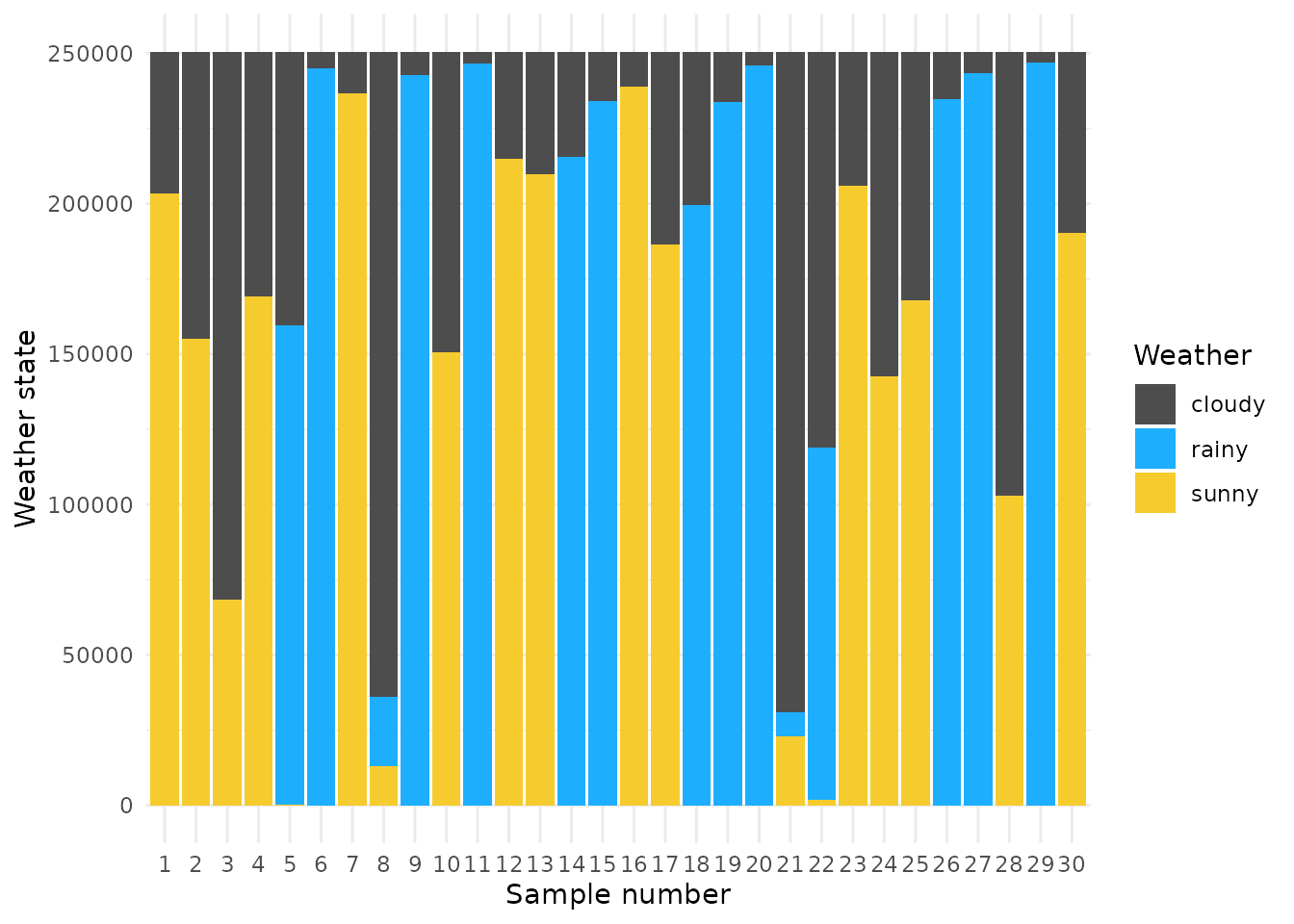

The next entry is post$discrete and is a list of

matrices describing the discrete states for each chain. These can be

easily plotted using ggplot2 also:

library(purrr)

df_discrete <- make_long_discrete(post$discrete)

weather_key <- c("1" = "rainy", "2" = "cloudy", "3" = "sunny")

df_discrete_plt <- df_discrete %>% mutate(value = recode(value, !!!weather_key)) %>%

mutate(idx = factor(idx, levels = 1:30))

df_discrete_plt %>%

ggplot() +

geom_col(aes(x = idx, y = sample_no, fill = factor(value))) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("sunny" = "#f6cb2e", "cloudy" = "gray30", "rainy" = "#1eaefe")) +

theme_minimal() + labs(x = "Sample number", y = "Weather state", fill = "Weather")

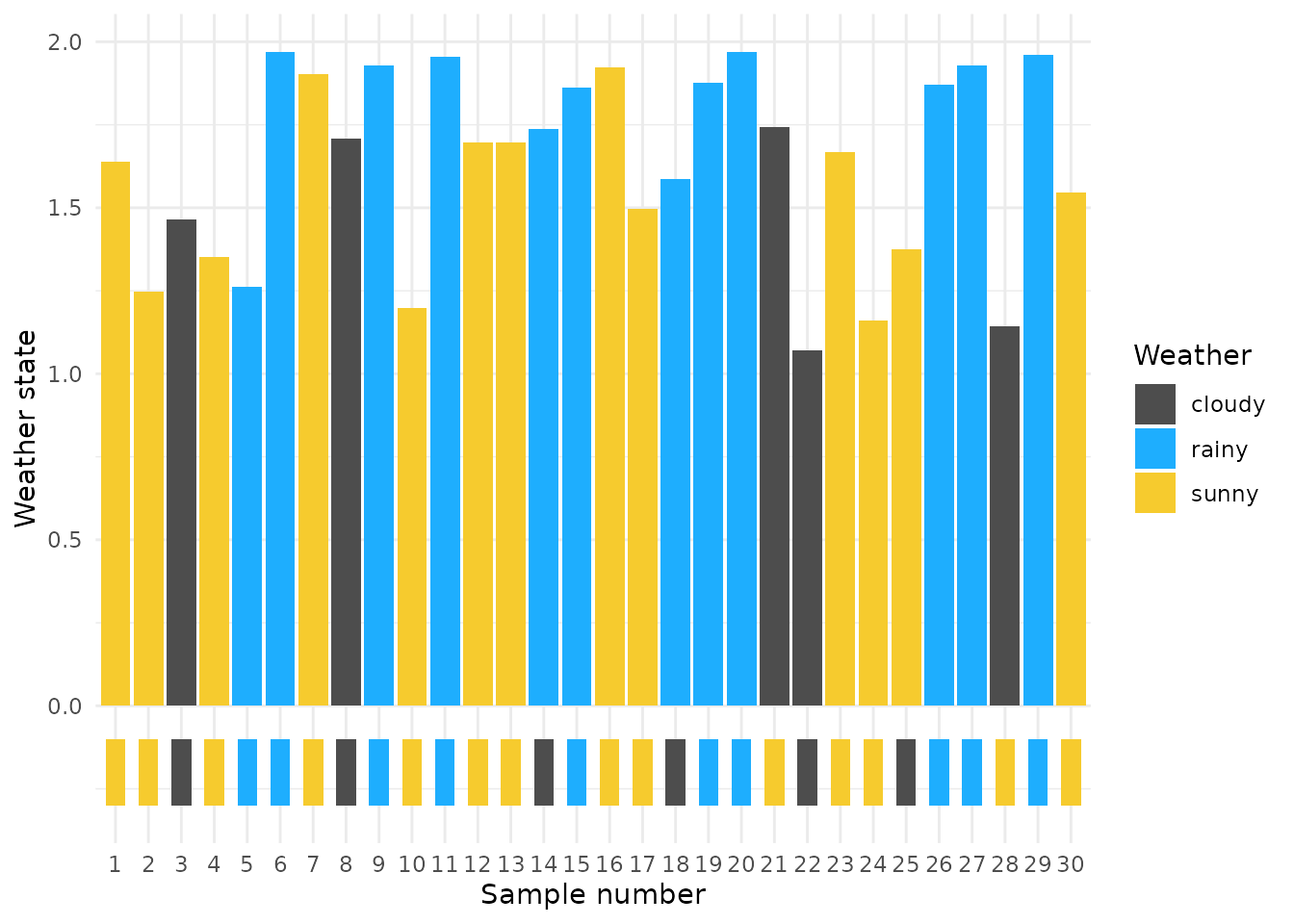

Let’s find the most probable weather state for each day based on the posterior samples and compare it to the true weather state (box color below 0.0)

recode_emoji <- c("sunny" = "\U1F602", "cloudy" = "☁️", "rainy" = "🌧️")

recode_emoji_color <- c("sunny" = "#f6cb2e", "cloudy" = "gray30", "rainy" = "#1eaefe")

true_sim <- data.frame(

idx = 1:30,

true = latent_weather

) %>% mutate(color = recode(true, !!!recode_emoji_color)) %>%

mutate(true_emoji = recode(true, !!!recode_emoji))

S <- df_discrete_plt$sample_no %>% unique %>% length

df_discrete_plt_mode <- df_discrete_plt %>% group_by(idx, value) %>%

summarise(n = n() / S) %>% filter(n == max(n))

df_discrete_plt_mode %>%

ggplot() +

geom_col(aes(x = idx, y = n, fill = factor(value))) +

geom_rect(data = true_sim, aes(xmin = idx - 0.3, xmax = idx + 0.3, ymin = -0.3, ymax = -0.1, fill = true)) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("sunny" = "#f6cb2e", "cloudy" = "gray30", "rainy" = "#1eaefe")) +

theme_minimal() + labs(x = "Sample number", y = "Weather state", fill = "Weather")

## 5. simulation recovery metrics

Here are a few easy distance metrics to compare the true and recovered weather states.

5.1. Simple Matching Coefficient (SMC)

The SMC calculates the proportion otrue_sim f elements in the vectors that match exactly.

recode_number <- c("sunny" = "3", "cloudy" = "2", "rainy" = "1")

true_vec <- true_sim %>% mutate(true_num = recode(true, !!!recode_number)) %>% pull(true_num)

model_est_vec <- df_discrete_plt_mode %>% mutate(value_num = recode(value, !!!recode_number)) %>% pull(value_num)

# SMC calculation

smc <- sum(true_vec == model_est_vec) / length(true_vec)

smc## [1] 0.8